The Silver Bullet of Anti-Shooter Educational Technologies

By Marie Heath and Aman Yadav

After the brutal mass murder of school children in Uvalde, Rick Smith, Axon’s CEO, said he and his wife clung to each other wondering, “what if that was our kids?” In response, he turned to his own skill set, knowledge, and business, arguing for taser-drones in schools that might disable a shooter within 60 seconds.

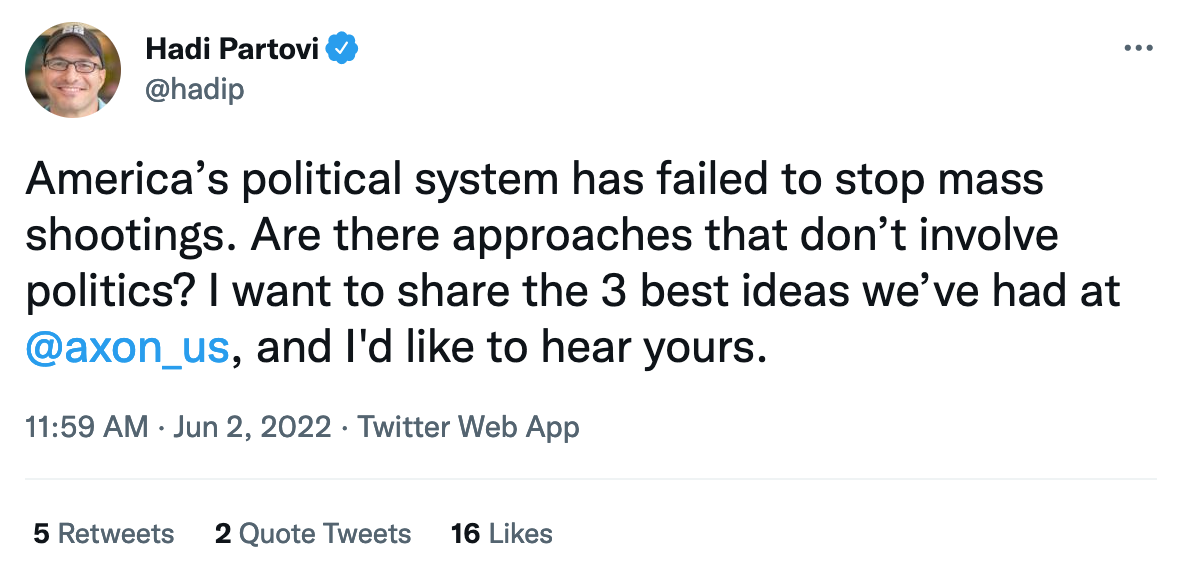

Partovi’s June 2, 2022, tweet asking for technological, instead of “political,” ideas to stop mass shootings

We can sympathize with this impulse. Marie has three school aged children and is married to a middle school teacher. Aman has two school-aged children and works with educators in school buildings. We live with the daily low-frequency buzz of anxiety that spikes to a nauseating roar after each school shooting report. The impulse to cling to any solution which calms our nerves and staunches our grief is real. Losing a loved one to gun violence is not an unreasonable worry. In 2020, guns resulted in 45,222 dead people in the U.S., and mass shooting events in the U.S. continue to increase in number. As citizens we have a moral obligation to act to prevent gun violence and the needless death of children in U.S. schools.

We also believe that as educators, and educators with a particular interest in technology, democracy, and justice, we have a further obligation to address gun violence in schools. As Audrey Watters argued in 2018, anti-shooter technologies, from locking doors to metal detectors to school shooting simulation software, are all educational technologies. But are these educational technologies that move us toward a just future? Do they address the complex social sickness of gun violence? Will they make schools a safe place for all children to learn?

Rick Smith, and many other leaders in technology companies, are advocating for their police technology (note, they refer to it as “public safety technology”) to become an educational technology. The founder of Code.org, Hadi Partovi, who sits on the Axon board of directors, also tweeted that technology can provide a solution to school shootings by connecting school cameras to law enforcement, using VR to train police officers, and using non-lethal drones as preventative tools. The problem is, many of these technologies have already failed. Techno-solutionist approaches to gun violence and school shooters have been implemented for over 20 years now in schools, and they don’t work. Further, they misdirect attention away from meaningful solutions by dangling shiny (and profit-increasing) promises of technology.

Anti-shooter educational technologies fail to prevent shootings. Moreover, they cause material harm to vulnerable students. The technologies themselves carry within them logics of oppression and carceral pedagogies (consider an educational technological audit of metal detectors, or see-through backpacks, or the proposed technology of surveillance cameras linked to law enforcement). In addition, the technologies are implemented in places and spaces shaped by power. It is no surprise that surveillance in schools causes harm to Black and Brown students. Surveillance of children’s keystrokes and social media harms vulnerable kids and fails to prevent school shootings. Armed police officers in schools are ineffective against school shooters and increase the likelihood that Black students are harmed in school.

Tweet from Hadi Partovi, Board Member of Axon and CEO of Code.org, advocating for 3 “non-political” technological solutions to mass shootings

Further, anti-shooter educational technologies allow people to insist that technology can save society without addressing underlying societal issues. Partovi’s tweet implies that solutions exist that aren’t “political.” Let’s set aside for a moment the presumption that the carceral technologies Partovi advocates for somehow lack an inherent political logic — tasers, wielded by people in power, be they police, teachers, or “remote drone operators,” harm and kill disproportionate numbers of Black people and disabled people, and in a Dallas school, a seven-year disabled child was tased and handcuffed. The notion that we could somehow sidestep politics to solve a complex social problem minimizes the complexity of our disease. The promise of an anti-shooter educational technology shifts our collective gaze away from the problem of a culture of reactionary racist and patriarchal violence in the U.S. and the uniquely American obsession with guns. Rick Smith, Hadi Partovi, and others dangle easy, though expensive, solutions in front of our eyes. They make millions of dollars as schools find ways to fund anti-shooter technology at the expense of social approaches and social emotional learning.

While we feel confident that increased surveillance, VR anti-shooter training, and taser-drone educational technologies make our schools less safe and less just, we continue to work toward other large and small solutions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified gun violence as a public health crisis, and we see this as one way forward. This framing encourages a comprehensive approach, which considers the complex social factors contributing to violence. This doesn’t rule out technological approaches -- and relatedly, we believe it is worth examining guns as a technology in society -- but it does acknowledge that gun violence is a complex problem that cannot be solved with a technological silver bullet. We understand the temptation to find such a weapon. However, we are working through our grief with a practice of hope through collective action.

Some of the groups we have supported include: Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, Everytown for Gun Safety, and March for Our Lives. And we will continue to advocate against increased surveillance as an educational technology to “solve” school shootings. As educators, how are you managing this time of grief? What resources and actions do you recommend? We look forward to continuing this conversation in the comments.