New Lesson: Lewis Latimer and the Invention of the Electric Light Inquiry

Civics of Tech Announcements

Apologies for Late Start on June Tech Talk: I want to also offer an apology here to anyone who tried to join our June Tech Talk. It was my (Dan’s) fault. I was visiting family in a different timezone and lost track of time, thus starting the talk 20 minutes late. I am sorry for those of you who missed it due to my error! It won’t happen again.

3rd Annual Conference Announcement: We are excited to announce that our third annual Civics of Technology conference will be held online on August 1st, from 11-4 pm EST and on August 2nd, 2024 from 11-3pm! Our featured keynotes will be Dr. Tiera Tanksley and Mr. Brian Merchant. You can register, submit proposals, and learn more on our 2024 conference page. Proposals are due this week—by June 14th!

June Book Club on Tuesday, 06/18/24: For our next book club we will Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein! The book club will be led by Dr. Marie Heath. We will meet at 8pm EDT on Tuesday, June 18th, 2024. You can register on our events page. Another summer book club is coming too.

Monthly Tech Talk on Tuesday, 07/11/24. Join our monthly tech talks to discuss current events, articles, books, podcast, or whatever we choose related to technology and education. There is no agenda or schedule. To avoid July 4th holiday conflicts, our next Tech Talk will be on Tuesday, July 9th, 2024 at 8-9pm EST/7-8pm CST/6-7pm MST/5-6pm PST. Learn more on our Events page and register to participate.

by Daniel G. Krutka

A couple weeks ago I was fortunate enough to be invited by my colleague, Dr. Queshonda Kudaisi, to teach a lesson at her STEM summer camp for middle school students. The camp focused on supporting students of color to “use STEM to understand the history, advantages, and disadvantages of the electric light in society. At the end of the camp, students will present research and innovation projects about a topic related to the electric light that interests them.” Another one of our colleagues, Dr. Chris Long, led students in an IEEE REACH experiment where students made a light bulb with batteries, and Dr. Kudaisi explored issues such as light pollution too. The camp was a great example of how STEM can attend to societal effects of technology.

For my part, I had 2.5 hours to teach an Inquiry Design Model (IDM) unit built around the compelling question, what story should we tell about electric lights? Civics of Tech participants may know that while I love interrogating new technologies such as generative AI, I also love to interrogate the supposedly more mundane and older technologies that are often treated as natural to our world. My journey in writing this lesson started in my search for picture books that could encourage technoskeptical thinking in elementary school. I eventually found John Rocco’s 2011 picture book, Blackout. As I write in a forthcoming article:

The book tells the story of a family living in a city who are “much too busy” as electricity powers their lights and devices that they each use in isolation. Once the power goes out, family members gather together without the pull of their devices, go outside to view the stars as light pollution is diminished, and join community members in the street.

The Inquiry Design Model (IDM) Blueprint previews the lesson.

As I started using this book with elementary teacher candidates, I became more interested in the history of electric lights and came across a name I hadn’t heard: Lewis H. Latimer. As I describe:

Lewis Howard Latimer was born in 1848 to Rebecca and George Latimer. Through hiding and disguise, his parents self-emancipated from slavery in Virginia because they did not want to raise their children in slavery. However, George was soon identified and jailed once they reached Boston. First the Black community and then the larger abolitionist movement championed George’s case by holding “Latimer meetings,” distributing “Latimer petitions,” creating “The Latimer Journal, and North Star,” and passing the 1843 Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act known as the “Latimer Law.” This law prevented the Massachusetts government from detaining people who escaped enslavement, but it was shortly thereafter overturned by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

My lesson includes sources that:

…focus primarily on providing an overview of Lewis Latimer’s life from his time as a soldier in the Union navy during the Civil War to his rise as a patent draftsman and inventor who worked alongside Alexander Graham Bell, Hiram Maxim, and Thomas Edison. Students should read the two-page biography of Latimer’s life and then watch a 6-minute video. Students can compare the two secondary sources and answer, who was Lewis Latimer? in small groups by writing down facts about his life. Students can identify different roles of Lewis Latimer’s life such as: Civil War veteran, draftsman, inventor, poet, husband, and father. Students should also learn about how Latimer experienced Black joy through family, poetry, and music. This shows that oppressive structures of white supremacy and segregation did not define Black people’s lives, but encourages students to think about the “full range of Black people’s emotions.”

The lesson encourages students to explore Elementary Black Historical Consciousness principles developed by Dr. LaGarrett King. I further explain:

Latimer faced anti-Black racism throughout his career as employment opportunities were limited and his abilities questioned by co-workers and subordinates, especially during his time in England. Yet, Latimer’s story offers a rare example of a Black man of his time who gained some level of acceptance within the electric light industry dominated by white men. He worked first at Hiram Maxim’s U.S. Electric Lighting Company and then for Maxim’s competitor Thomas Edison at General Electric. Latimer may have partially succeeded during a time of segregation because he was not as vocal for racial justice.

Latimer’s beliefs about race can be characterized as assimilationist. In letters to Booker T. Washington, he expressed views that suggested that Black people were not inherently created equal, but that they had to prove to white people they were “civilized.” Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi described assimilationist racism in a way young learners can understand as “people who like you… if you’re like them.” This can be contrasted with an antiracist view where people “love you because you’re like you.” Latimer tended to communicate and identify with other elite Black leaders, but he was less involved in Black movements for full equality.

I provide this historical context for teachers because as students learn more about this time period, they may wonder how a Black man navigated a racist society. Teachers can help upper elementary students both cultivate racial consciousness and think historically by discussing white supremacy, and different views on how to address it in the Black community of Latimer’s time. The son of previously enslaved parents, Latimer overcame significant racial barriers in his life to achieve professional and personal success, but this does not mean that he was a perfect hero.

More than any other part of the article, I wrestled with how to characterize and teach about Latimer’s racial politics. As I shared in a previous blog post reviewing Rayvon Fouché’s 2003 book Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation:Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J. Davidson, the stories of Black inventors are often more complex than they are portrayed as in schools and popular media. Just last year, Congresswoman Grace Meng of New York’s 6th district introduced legislation for a commemorative postage stamp in honor of Latimer. In her press release, she said, Latimer’s “advancement of civil rights for Black Americans cannot be understated.” As Fouché pointed out with his “Black Inventor Myth,” many Black inventors did not pursue their work to contribute to racial uplift. Why is it assumed that Black inventors were also civil rights activists? This seems to be the case for Latimer. Yet, I often am careful to recognize that Latimer could have lost everything if he had been more vocal for Black civil rights. The point for students is not to cast judgment on Latimer from the present, but to understand the impossible environment which Inventors of Color have long had to navigate. Timnit Gebru’s case offers a contemporary example of the consequences of advocating for justice in Silicon Valley.

The final part of my journey in organizing this lesson was to confront the sole inventor myth that “Edison invented the lightbulb.” In recent years, I have noticed a tendency to either give Edison all the credit or none of it, with this latter claim noting that he simply stole others’ ideas. The truth is somewhere in between while recognizing there are plenty of reasons to critique Edison’s methods. Latimer’s contributions to the lightbulb provide just one example of how invention is a social process that involves many people. As part of the lesson, I also have students review light bulb patents and watch a History Channel video that better contextualizes what Thomas Edison did and didn’t do alongside many other lightbulb “inventors” such as Frederick de Moleyns and Joseph Swan. Most students were able to provide a more nuanced answer to my question, who invented the lightbulb?, after reviewing and discussing the sources.

There’s a lot more to this lesson, but I won’t detail it all here because you can find the full inquiry on our site. The lesson includes primary and secondary sources, a guiding worksheet, and much more if you’d like to teach the lesson. It also includes a pre-print of a forthcoming article on the lesson to be published in Social Studies and the Young Learner in January 2025.

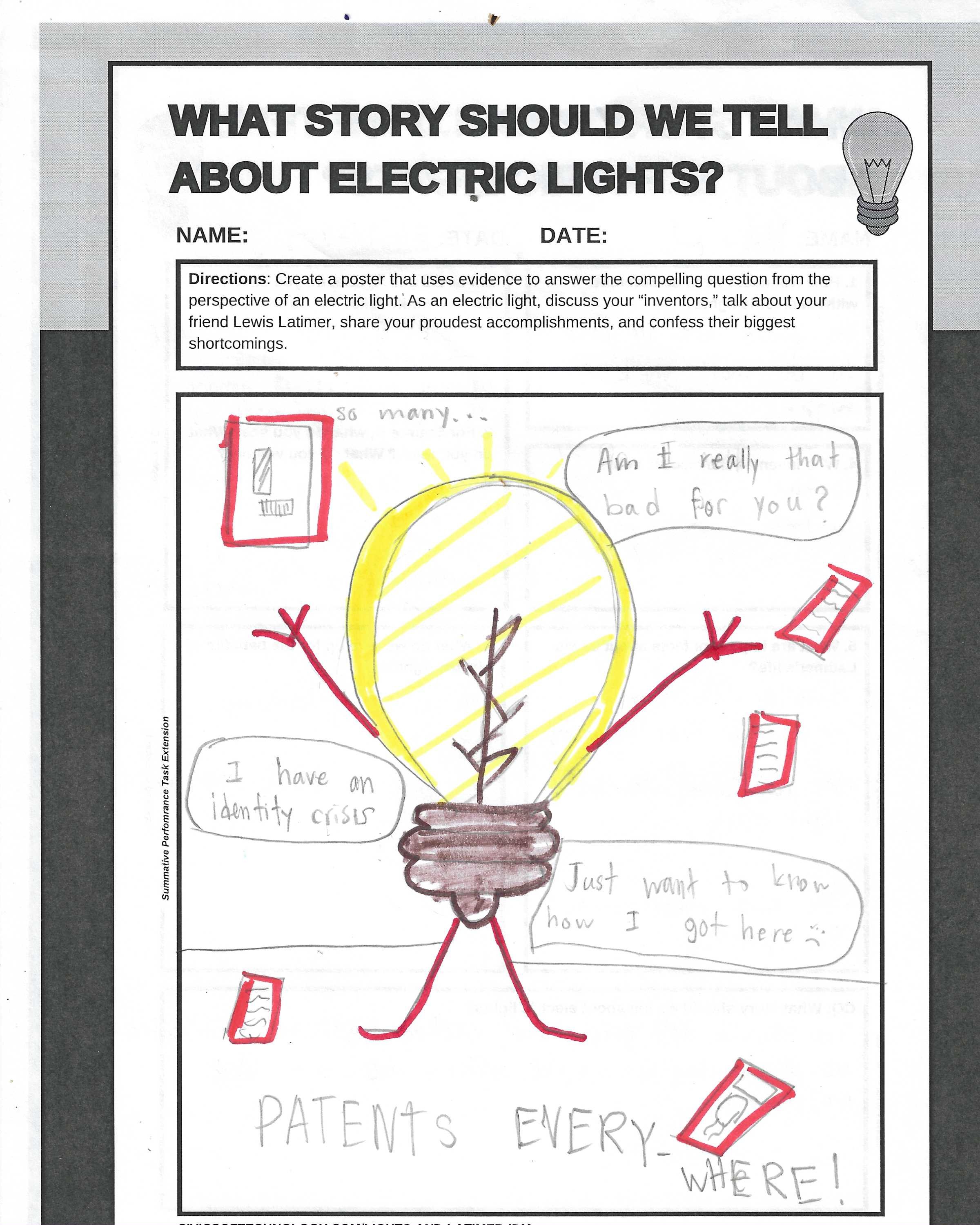

This student drawing (shared with permission) shows their answer to the compelling question from the perspective of an anthropomorphic lightbulb.

The only thing more fun than researching and writing this inquiry was teaching it with students. I have taught it to over 10 groups of students, including Dr. Kudaisi’s middle school STEM camp students. I was so impressed during the inquiry of their ability to provide complex and thoughtful answers to questions concerning the nature of invention, the meaning of Lewis Latimer’s life, and the role electric lights should play in our lives. I learned a lot from them. And I hope it helped them think a bit differently about technology too.

References

Fouché, R. (2005). Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J. Davidson. John Hopkins University Press.

Hao, K. (2020, December 4). We read the paper that forced Timnit Gebru out of Google. Here’s what it says. MIT Technology Review.

King, L. J. (2023). Introduction: How Do I Start Teaching Black History? Social Studies and the Young Learner, 35(3), 3-4.