Technology Decisions: Owning Unanticipated Consequences

Civics of Tech Announcements

Next Monthly Tech Talk on this Tuesday, 04/04/24. Join our monthly tech talks to discuss current events, articles, books, podcast, or whatever we choose related to technology and education. There is no agenda or schedule. Our next Tech Talk will be this Tuesday, April 4th, 2024 at 8-9pm EST/7-8pm CST/6-7pm MST/5-6pm PST. Learn more on our Events page and register to participate.

AERA24 Meet in Philadelphia, 04/12/24: Join us for a Civics of Technology Meet-Up on Friday, April 12th, 4pm @ Bar-Ly (http://www.bar-ly.com) in Philadelphia, PA. You can RSVP here, and we'll add you to a calendar invite. You’re welcome to bring friends! Read Marie's blog post about the event.

Next Book Club on Thursday, 4/25/24: Choose any book by Ruha Benjamin for #RuhaBookClubNight led by Dan Krutka. Register for this book club event if you’d like to participate.

by Jennifer Hylemon

One of my favorite podcasts is Cautionary Tales with Tim Harford, a British economist and journalist. His November 11th, 2022, episode fascinated me with its narrative about Thomas Midgley, a rather unfortunate figure in early 20th century U.S. history who pioneered not one but two disastrous environmental innovations, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and leaded gasoline. Midgley was also killed by one of his other inventions. What has stuck with me from this episode are that the consequences of these few of Midgley’s many inventions were completely unanticipated and Harford’s questions about whether they were also unintended.

Harford explains that the language of unanticipated consequences in sociological research dates back to a 1936 article by Robert K. Merton. However, the language of “unanticipated” fell out of favor over time and was generally replaced with “unintended” even in Merton’s own later work. I do not think these two ideas are the same thing at all. To say something is unintended shifts blame–I didn’t mean for that to happen, so it must not be my fault. To say something is unanticipated preserves accountability–I didn’t think about that before I acted, and I recognize that I am at fault.

Moreover, intent speaks to motive whereas anticipation speaks to forethought. Thinking in legal terms, they are the difference between convictions for first and second degree murder. The consequence of the action is that someone is dead. If the killing is intentional, the perpetrator can be found guilty of second degree murder. If it can additionally be proved that the perpetrator acted “with malice aforethought,” then they can be convicted of first degree murder.

Okay, calm down, this is educational technology we’re talking about, not life and death, right? Maybe ed tech never killed anyone, but if we took our decision-making processes about the use of technology in education as seriously as we take decisions that greatly affect not only our own lives but the lives of others, then we could make decisions that improve our society. So, how do we think about the decisions we make and their consequences?

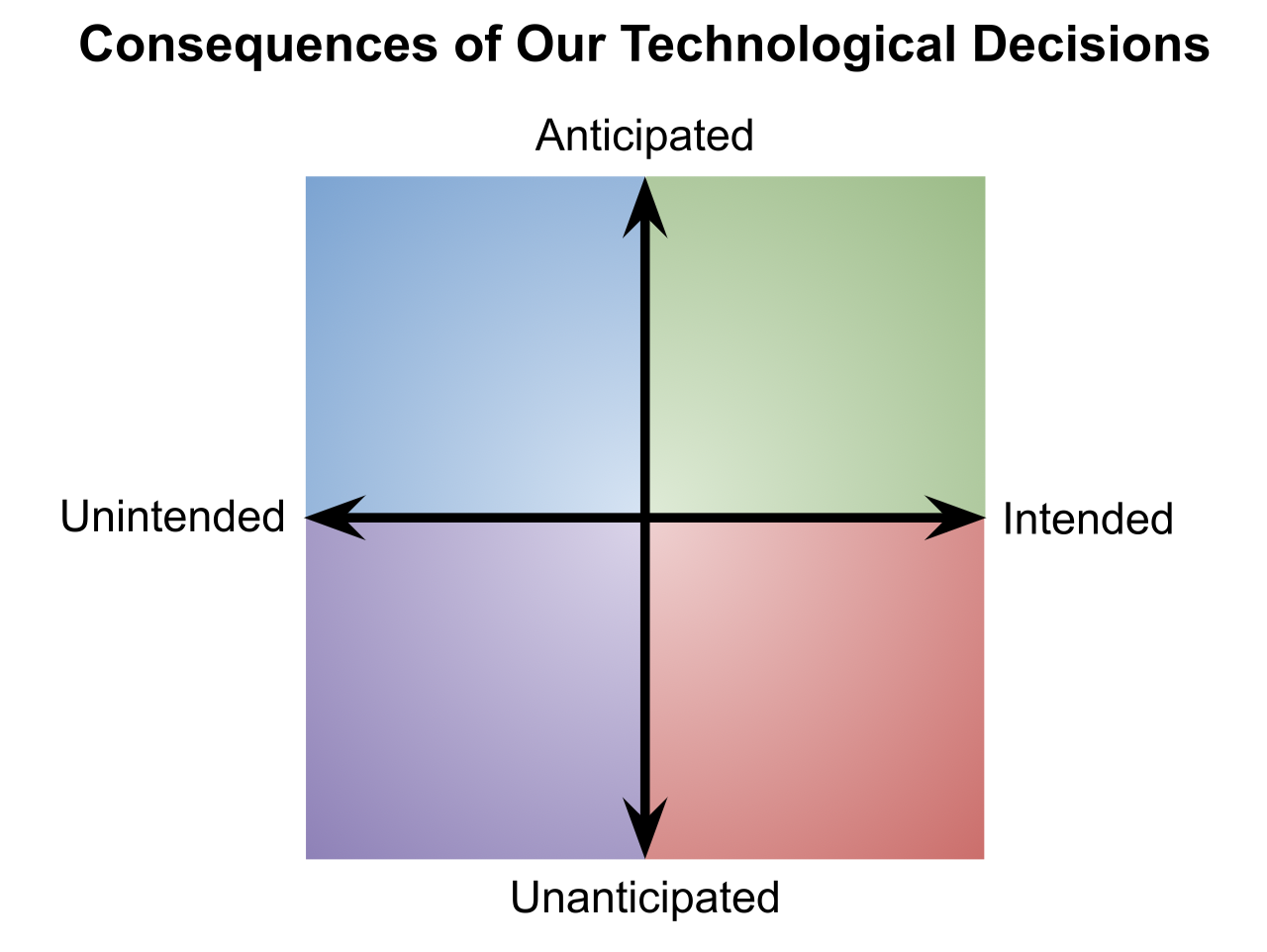

On the plane of consequences of our decisions about educational technology, I see intent and anticipation as existing in an overlaid Cartesian coordinate system with intent on the horizontal axis and anticipation on the vertical axis. This naturally divides the plane into four quadrants:

Quadrant I, the green zone, describes consequences we both intend and anticipate. These tend to be the positive consequences of the decision to use the technology of interest in education.

Quadrant II, the blue zone, describes consequences we do not intend but do anticipate.

Quadrant III, the purple zone, describes consequences of the decision to use the technology of interest that we don’t intend and don’t anticipate. These tend to be the things we never thought about and also did not want to happen as a result of our decision.

Quadrant IV, the red zone, describes consequences we intend but do not anticipate. This seems paradoxically to mean for something to happen without thinking about it, but that’s how dominant groups and the technology sector generally operate in U.S. society on a daily basis, making it unsurprising for that attitude toward decision-making to show up in the consequences of our decisions about technology in education.

Visualization of consequences of actions taken regarding technology in education.

Efficiency > Humanity in Technological Design

Putting efficiency over human needs and rights often puts us in the red zone of the graph in which our focus on outcomes overlooks consequences we should have anticipated in the first place because they were actually intended but not considered. Ruha Benjamin’s brilliant 2019 book Race After Technology provides a plethora of examples of cases where efficiency was valued over humanity. One of the most shocking of these is in the photography industry. Due to the overrepresentation of white engineers at Kodak, the settings for skin tone on what were known as Shirley cards were incorrectly calibrated for darker skin tones. It took complaints from–get this–manufacturers of wooden furniture and chocolate candy to change industry standards regarding how the variations of the color brown showed up in photographs. I’m just going to pause a moment to let that sink in. …And lest you think the bias is merely historical, it continues today in technology that requires human activation such as soap dispensers that fail to activate for darker skin and facial recognition software that consistently recognize white faces at a higher rate than Black faces as seen in the documentary Coded Bias.

Educators often use the technology of a learning management system (LMS) such as Canvas, Schoology, or Google Classroom, to organize course materials, collect assignments, etc. Many times our decision about its use is designed for the efficiency of the instructor. I’m going to organize the course in a way that makes sense for me because as its instructor, I will need to use this course shell again. However, an unanticipated but entirely intended consequence of this thought process is lack of care about the students who interact with the course. In working with teachers, we organized Canvas course shells with one module per unit in the order in which they would be taught with all the materials unpublished but ready to be published. In working with students, we discovered that publishing only selected materials at the outset, publishing others along the way, and ordering the modules with the one matching current instruction at the top of the list of modules improved the student experience. As an instructor at the undergraduate level using an LMS, I now make decisions about course structure with both stakeholders in mind, taking student feedback into account along the way. Course structure is not a one-time decision, but a series of decisions that sometimes change depending on the needs of the students.

Haste Makes Waste

In public education, decisions are often made in haste, especially during budget season. I made one of those hasty decisions during my time in educational administration. Our district contract for instructional materials was coming to an end and I needed to decide how to move forward, but I had some time to do so. However, our current materials publisher reached out in early December with a deal that would save us millions of dollars if we acted quickly. I knew this was money we were going to be spending one way or another. I asked our technology department to run a quick usage report for me and was surprised to learn that more teachers and students were using the materials than I had thought. Therefore, I sprang into action to push the purchase through before January 1.

I thought I was squarely in the green zone, anticipating happiness at the maintenance of the status quo–teachers, students, and parents would all continue to have access to the excellent resources committees had chosen many years before. I was actually living in that purple zone without realizing it. All I was thinking about was keeping consistent resources in the virtual hands of teachers and students, and saving the district money. That required moving fast. Had I slowed down and considered that I was foregrounding efficiency, I would have realized that I wasn’t thinking about whether those were the right resources to continue to support. Furthermore, I did not analyze any publicly available data that would have informed me about the shortcomings of these resources.

I should have pulled a group of interested and diverse stakeholders together to consider whether there were any better resources out there. I did not even consider the resources our state was making available for a limited time free of charge to school districts that would have met my goal of saving the district money. Now, I also didn’t intend for inequities that had been the case with these adopted resources all along to be perpetuated, such as lack of support for multilingual learners, but that was absolutely a consequence of my decision. I did not intend to deprive teachers and students of new resources that could potentially have improved student outcomes, but I must own the continuation of flat accountability outcomes that did occur as a result of my decision.

Technology Changes Things… and People

Neil Postman observed that changes involving technologies don’t merely change one thing–they change everything. Technology evolves into the new normal with each generation. My generation was the first to have personal computers. Today, children live in a society that expects not just a single device in the house but their own dedicated device that is portable. As technology changes us, are we evolving into people who personally benefit so much from technology that we ignore its deleterious effects on our society, especially in education? Does that then have us living unwittingly in the purple and red zones where we don’t anticipate any consequences of our technological actions, intended or otherwise? Because we don’t feel there is a decision to be made–the technological solution is so ingrained that no problem is perceived.

Take the use of graphing calculators in upper middle school and high school mathematics as an example. Graphing calculator technologies such as TI-84 Plus CE, Desmos, TI-Nspire, and Geogebra are available to students in classrooms as early as 8th grade where I live, perhaps even earlier for instructional use. Standardized testing doesn’t allow its use until grade 8, so that is where it tends to be introduced in public education. I mention testing because the premium that is placed on student outcomes on such assessments, and their direct impact on campus accountability ratings, highly influences teacher decisions about the use of such technology in the mathematics classroom. The technology can produce highly accurate graphs in much less time than it takes students to produce them by hand. Therefore, students spend much less time analyzing the relationships in graphs necessary to produce them accurately. This results in students having more shallow knowledge about graphs in general and functions in particular. Large numbers of students are able to produce images digitally that they cannot produce by hand without seeing the digital image first. And that’s okay by the testing standards since interpretation is the premium, and the picture of the graph either is provided in the item stimulus or the digital graphing tool to produce the graph is provided. This feeds the vicious cycle of the assessment tail wagging the instructional dog, so to speak. The testing agency even reframed its calculator policy in reaction to media coverage about this issue. Without thinking that considers the ecological impact of technological decisions, what occurs is an overabundance of trust in the technology to the detriment of student learning, but not performance outcomes.

Blue Sky Thinking

Anticipating what we don’t intend is a lot to ask, but y’all, we’re educators. If we aren’t actively learning to make better decisions, how can we hold our students to the standard of making good choices? Shifting our focus to include analysis of unanticipated consequences of new technologies and resources will help us choose the best options for ourselves and students. Hitting that blue zone requires us to think deeply and critically about our actions regarding technology in education. We must consider issues from multiple perspectives outside our own and chase rabbit trails of possible outcomes whether good or bad. Blue sky thinking is required. Such thinking is usually reserved for imagining possible futures and I contend that is highly applicable to decision making about technology in education. What will my classroom look like if I do choose this technology, or use this technology in that particular way? What will it look like if I don’t?

It requires empathy to step into the shoes of our students and imagine their experience of our technological decisions. We should seek other people’s opinions and learn from their wisdom. We need to ask not just how our students will be impacted but rather, How will this particular student with their unique educational needs be impacted by my choice regarding technology in this educational moment? That question needs to be on loop in our heads because decisions about technology in education are ongoing and always malleable. We can also project possible future impacts with questions such as, If I use this technology in this way now, how am I empowering students for their future? Conversely, How am I impairing their future learning with this use of technology? If we as teachers who make thousands of decisions a day can filter those decisions about technology through the dual lenses of anticipation and intent, there might just be blue skies ahead for the educational ecosystem.

References

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology. Polity Press.

Futureism. (2017, August 18). This ‘Racist soap dispenser’ at Facebook office does not work for black people [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YJjv_OeiHmo

Harford, T. (2022, November 11). The inventor who almost ended the world. Cautionary Tales podcast. https://timharford.com/2022/11/cautionary-tales-the-inventor-who-almost-ended-the-world/

Kantayya, S. (Director). (2020). Coded bias [Film]. 7th Empire Media.

Postman, N. (1992). Technolopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. Vintage Books.

Texas Education Agency. (2024). Texas Resource Review. https://texasresourcereview.org/